- Home

- Duberman, Martin

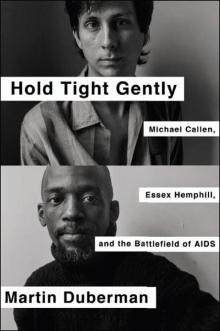

Hold Tight Gently

Hold Tight Gently Read online

HOLD TIGHT GENTLY

ALSO BY MARTIN DUBERMAN

NONFICTION

Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left

A Saving Remnant:

The Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds

Waiting to Land: A (Mostly) Political Memoir

The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein

Left Out: The Politics of Exclusion: Essays 1964–2002

Queer Representations (editor)

A Queer World (editor)

Midlife Queer: Autobiography of a Decade, 1971–1981

Stonewall

Cures: A Gay Man’s Odyssey

Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past (co-editor)

Paul Robeson: A Biography

About Time: Exploring the Gay Past

Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community

The Uncompleted Past

James Russell Lowell

The Antislavery Vanguard (editor)

Charles Francis Adams, 1807–1886

DRAMA

Radical Acts

Male Armor: Selected Plays, 1968–1974

The Memory Bank

FICTION

Haymarket

HOLD

TIGHT

GENTLY

Michael Callen, Essex Hemphill,

and the Battlefield of AIDS

Martin Duberman

© 2014 by Martin Duberman

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2014

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

CIP data available

ISBN 978-1-59558-965-1 (e-book)

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by Westchester Book Composition

This book was set in Janson Text

24681097531

To the memory of those lost to AIDS

There’s a certain slant of light,

On winter afternoons,

That oppresses, like the weight

Of cathedral tunes.

Heavenly hurt it gives us;

We can find no scar,

But internal difference

Where the meanings are. . . .

—Emily Dickinson

Contents

INTRODUCTION

1. Before the Storm

2. Reading the Signs

3. Career Moves

4. The Mideighties

5. The Toll Mounts

6. Drugs into Bodies

7. Stalemate

8. Breaking Down

9. Wartime

10. Home

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

INDEX

Introduction

Since the midnineties, public concern in the United States about the AIDS pandemic has continued to decline, even as the disease continues to spread. The number of Americans who consider AIDS the most urgent health problem facing the nation dropped from 44 percent in 1995 to 6 percent in 2009. One reason, surely, is that AIDS has become less and less a white disease and more and more a disease associated with people of color. Globally, fewer than half the people afflicted with AIDS are receiving treatment, and in light of recent budget cuts reducing AIDS expenditures, that number is likely to decline further. Even in the most “developed” countries, suppression of HIV through antiretroviral medication remains incompletely effective.

In its most recent (May 2012) report, with data through 2009, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) shows a vast disparity of new infections among racial-ethnic groups in the United States. Though African Americans make up only 12 percent of the population, black men who sleep with men account for 45 percent of new AIDS diagnoses. This is despite the fact that young gay black men have fewer partners, less unprotected sex, and lower rates of recreational drug use than other gay men. Some Latino men who sleep with men—who made up 20 percent of new AIDS diagnoses in 2009—like some African American men do not primarily self-identify as gay (not least because many consider “gay” a white term). Those who sleep with women as well as men help to account—especially in hot-spot cities such as Washington, D.C.—for the recent realization that new HIV and AIDs cases among African American women are now comparable to rates for women in sub-Saharan Africa. Infection rates continue to rise among white gay men as well, but the mortality rates aren’t comparable: the proportion of deaths among whites (and especially among those with high levels of education—and the income and access that follow) has declined, but HIV and AIDS among men and women of color in the United States of all sexual preferences continues to skyrocket, especially among lower-income populations. African American women are now dying at fifteen times the rate white women do. Self-identified gay men of all colors, however, are still fifty times more likely to contract AIDS than any other demographic group.

One would expect to find mainstream LGBT organizations and spokespeople still vociferously active in pressuring pharmaceutical companies and researchers to come up with better treatments and preventative strategies, and governmental agencies—the CDC, the National Institutes of Health—offering greater services to those already ill. But that isn’t the case. The sense of urgency among gay people themselves is seemingly gone; a portion of the new generation dislikes using condoms for safer sex and tells itself that with the advent of protease inhibitors, AIDS is now a “manageable” disease. It is, for those who can afford and who can tolerate the medications, though no one knows how long they’ll remain effective and what secondary damage they’re doing along the way; for some people the drugs don’t work at all, for others only briefly.

The older generations of white gay men who have physically survived the epidemic have buried their dead—and to a regrettable degree, their heads in the sand. As the longtime AIDS journalist John-Manuel Andriote has put it, the “traditional donors—middle-class and affluent white gay men—have ‘moved on’ since they can now get their HIV-related medical care from their private physicians. . . . The old ACT UP slogan of ‘Silence = Death’ still holds, if by ‘silence’ we mean withholding of support.” Since the midnineties the mainstream gay agenda has demoted AIDS from its top priority and replaced it with what those of us on the left call the assimilationist items of legal matrimony and the “patriotic” right to serve openly in the armed forces.

In Africa, AIDS is primarily a heterosexual phenomenon, but in the United States it remains a profoundly gay one, with poor, young, nonwhite men disproportionately impacted—though children, intravenous drug users, and heterosexual women are hardly immune. But self-identified gay men in the United States do still make up 48 percent of the 1 million people currently living with AIDS. We haven’t even reached the point where the annual increase in gay male patients being treated exceeds the number of gay men being newly infected.

My hope is that this book will shed additional light on our current approach to AIDS by scrutinizing more closely the earlier years (1981–95) of the epidemic, and in particular the pre–ACT UP (1987) period. I’ve chosen to tell this story through

the lives of two gay men, the singer and activist Michael (Mike) Callen and the poet and cultural worker Essex Hemphill. The two never met and had little in common. Mike was a white midwesterner who came to New York City after college to pursue a singing career. Essex was an African American gay man who grew up in Washington, D.C., and knew early that he wanted to become a writer, and specifically a poet.

Both men were diagnosed with AIDS early in the epidemic. Mike became a leading maverick in the organized efforts to fight the disease as one of the earliest originators of “safe sex” and the People with AIDS Self-Empowerment Movement. Essex largely avoided the white-dominated public protest campaign, primarily devoting himself to participating in and fostering the black gay male and lesbian cultural flowering in the 1980s now widely referred to as the “second Harlem Renaissance.” The experience of the AIDS epidemic was in critical ways dissimilar for the white gay community and the black gay one, and that distinction is one of the major themes of this book.

I knew both Mike and Essex, though only slightly. What I did know, I admired greatly—and I wanted to know more. I viewed Mike as an undersung hero of the AIDS protest movement and Essex as an undersung poet of major importance in black cultural circles. In Mike Callen’s case, the search for previously unknown material proved comparatively easy: not only did he have a temperament frank to the point of transparency—or, in the eyes of his detractors, to a fault—but he left behind a very large archive of letters, speeches, diary notes, organizational materials, and—as a performer and songwriter—lots of music.

Telling Essex Hemphill’s story proved more difficult. He left behind one published collection of poems; an anthology that he edited of writings by black gay men; appearances in Marlon Riggs’ and Isaac Julien’s films; and a smattering of correspondence, much of which remains in private hands. At the end of his life, Essex told a number of close friends that he wanted his papers to go to the Schomburg Center, the branch of the New York Public Library devoted to black culture. But they never arrived. My own polite letters of inquiry to Essex’s mother, Mantalene, went unanswered. However, she did, some fifteen years ago, send a batch of his letters and manuscripts to his literary agent, Frances Goldin. Luckily, I know Frances well; she generously gave me full access to the material, which it turns out includes the manuscript of Essex’s unpublished and presumed lost novel in progress, “Standing in the Gap.” I’ve quoted from portions of this treasure trove throughout the book. To further fill out Essex’s story, I’ve conducted lengthy interviews with many of his close friends and have also been given access to letters and other materials in private hands.

Essex’s temperament was considerably more guarded and enigmatic than Mike’s. A person of charismatic charm and mischievous guile, Essex could often be enchanting, but he keenly guarded his privacy and—while not at all prudish—persistently warded off those who probed for details about his personal attachments or the state of his health. He was so intent on protecting his inner life from unwanted scrutiny and so quick to react to any threat to his principles that some mistook this integrity for hauteur. His poetry, often autobiographical, makes it possible to map certain aspects of his inner life, yet I suspect that even if Essex had left behind a massive archive, it would most likely contain little about his intimate feelings and struggles.

For all these reasons, this book contains more personal information about Mike than about Essex; that reflects both the nature of their respective personalities and the kinds of material each left behind. Though they were very different from each other, I hold these two exceptional men in equal regard and have made an equal effort to bring their remarkable stories to life.

1

Before the Storm

Soon after Mike Callen completed college at Boston University in 1977, he moved to New York City, and soon after that, he became ill with shigella—intestinal parasites. At first, he thought he’d gotten food poisoning from the Kentucky Fried Chicken stand on Forty-Second Street that he frequented. Trying to shrug off and explain persistent, exhausting bouts of diarrhea, he told himself that he’d always been more or less sickly, which was true: as a sensitive, scrawny youngster in Hamilton, Ohio, he’d gotten an ulcer in the fifth grade, a second one in the eighth grade, and yet a third in the eleventh. Then, during high school, he’d been hospitalized twice, once with mononucleosis and once with hepatitis.1

A tender, hyperactive child, Mike was playing canasta with some older family friends one day—cheating and winning, “screeching” (his description) with delight—when one of the women put down her cards, gave him a stern look, and said, “If you don’t watch out, Michael, you’re going to become one of those homosexuals.” He had no idea what that meant, but he caught the overtones of imminent doom and realized that the prediction was meant to frighten him. Did that explain, he asked himself, why he often felt nervous and was repeatedly cautioned about being too “animated”? At age eight, for instance, he twirled a baton at the head of a neighborhood parade with such giddy glee that eyebrows were raised; and he remembered running into the house at a young age, “flapping his arms like a little sissy,” and his father slapping him hard across the face and yelling, “Don’t you ever do that again!”

The neighborhood lady’s use of the word “homosexual” piqued Mike’s curiosity and he decided to ask around. It turned out that everyone in the town of Hamilton knew that “homosexual” meant Delmore Knight, that “dirty old man” who hung around the Greyhound bus station and enticed young boys to do “nasty” things. Although Knight was said to have a doctorate from Oxford University and was even rumored to have won some academic prize, no one in Hamilton seemed to doubt that he deserved the regular beatings that a cadre of high school jocks dished out to him. Republican and evangelical, Hamilton was a Dixie border town known as well for its strict adherence to racial segregation. According to Jennifer Jackson, who went to high school with Mike, Hamilton was “a town with secrets, with a polite midwestern refusal to acknowledge how many were hurt and excluded,” exemplified by the crumbling Victorian Poor House Hill, which sat on a visible precipice, initially serving as a debtors’ prison, then an orphanage, then a home for the mentally ill—“a perfect storm of misery and entrapment.”2

When Mike and his brother, Barry, a year older, were in their early teens, their parents decided the time had come to tell them about “the facts of life” (their younger sister, Linda, was exempted from the talk). The boys’ mother, Barbara Ann, was a part-time elementary school teacher and their father, Clifford, a factory worker at General Motors. Both were deeply religious Baptists and the topic of sex was at least as embarrassing to them as to their two young sons. During her part of the “birds and the bees” session, Barbara fell back on traditional church teachings. Mike remembered her saying that sex was “dirty and disgusting, messy and a bother, but beautiful if it resulted in a child.” After the three children had been born, she and Cliff still had sex once a week to prevent him from getting headaches and hemorrhoids, or turning grumpy.

Mike’s father uncomfortably expanded on the theme: “The man puts his penis inside the woman and they make a baby,” he told the two boys. “Do you understand?” Cliff asked. Barry, who’d broken out in a cold sweat, nodded yes. Mike, bright and stubbornly outspoken, said he was confused; why, he asked, should he concern himself with putting his penis “inside some stupid girl and peeing inside her just to make a baby; what if the baby turned out to be dumb like my sister?”

Cliff’s response was a non sequitur: “Never be afraid to ask us anything.” Fine, except that Mike’s main fear was his father himself. He always “smelled of grease”—Cliff worked at GM’s Fisher Body, welding doors—and was remote and unemotional. Mike became convinced that his father “hated” him and often dreamed that Cliff was stabbing him “with one of those cheap steak knives they kept giving us free for a fill-up at Shell.” His closed-down, evasive father was, in fact, a decent, if embittered, man, liberal (considering his time and place)

in his political views and struggling to understand his children—though as a devout Baptist he would always find homosexuality repulsive, even immoral.

Life hadn’t been easy for Cliff. After his own father’s early death, he’d had to forgo college to support his mother and sister. After he married Barbara Ann and had children of his own, he worked ten hours a day, seven days a week, at GM—enduring a ninety-mile daily commute round-trip. According to Barbara Ann, he refused every chance to climb the corporate ladder since he felt that would entail the “sacrifice of his beliefs and his morals,” would force him, if he became a foreman or superintendent, to treat employees below him in a “degrading and demeaning” manner that would make them “feel like just so many cattle.”

Cliff dreamed of leaving GM altogether, but every idea he had of another way to make a living—starting a restaurant, moving to Arizona to open a small store—somehow broke down. He struggled to avoid seeing himself as a failure, but the effort further closed him off emotionally, made him a hard-shell Baptist in all but name. Trapped himself, he “forced” (as Mike saw it) his wife, Barbara Ann, to go to college and get a teaching certificate, though she preferred being a stay-at-home mom. They’d had “terrific fights” about it and Barbara Ann finally yielded, but in her unhappiness she put on a great deal of weight and according to Mike “had a nervous breakdown.”

During his senior year in high school Mike took over the running of the house and did all the shopping, cooking, and cleaning, with little assistance from his siblings. (Cooking would become a lifelong pleasure for him; he deeply associated it with “sensuality and hedonism,” and he reveled in “cooking for his man.”) In retrospect, he felt the “housewife” role had been thrust on him, or perhaps he assumed it, because he was frequently mocked in high school as a “sissy,” a sort of substitute woman. He had his admirers: Jennifer Jackson, two years behind Mike, was one of them. She recalls his sensitive response to her one day when he spotted her standing in line to audition for a school play, “twisting and turning behind the curtain, ready to run.” Mike went over to her, asked her if she’d ever acted before (she hadn’t), and drew her out about her difficult background and family life. “He listened,” Jackson recalls, “and he wouldn’t let you stand there feeling alone and irrelevant. He sensed despair somehow and didn’t turn away. . . . There he was, with those hands waving around, perfectly articulate, telling me things wouldn’t be okay, but eventually I’d get out of Hamilton somehow.” She never forgot his kindness.

Hold Tight Gently

Hold Tight Gently